By Joe Hussein

The story begins in the 1950s, when a bold operator named Johnstone shook Salisbury’s transport scene.

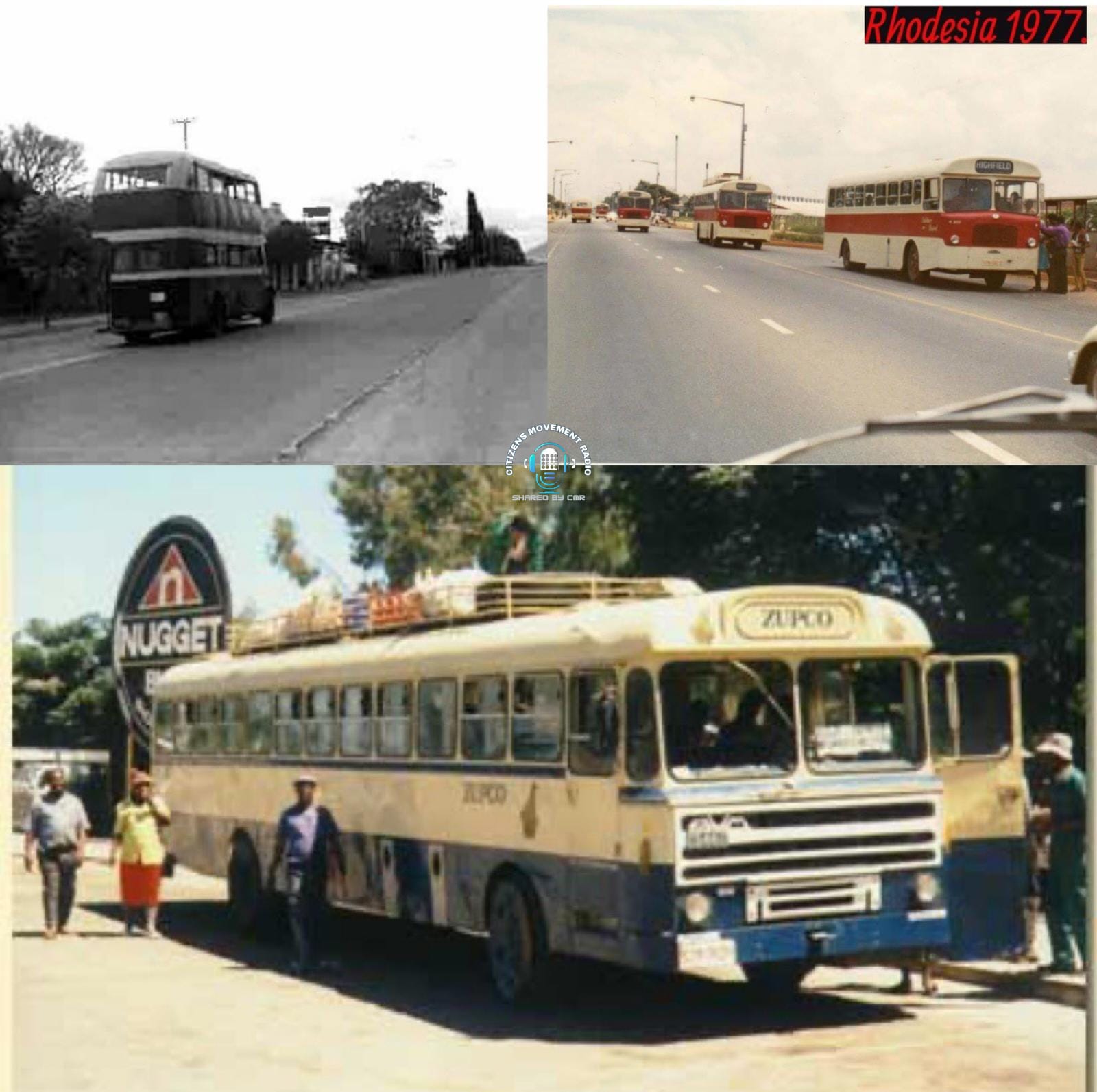

He imported twenty double-decker buses from London and branded his new company TransRhodes. When he tested the buses in Harari (now Mbare), the locals took one look at the towering machines and immediately nicknamed them “upstairs–downstairs,” comparing them to the split-level houses in whites-only suburbs.

The joke stuck, and TransRhodes became township folklore overnight.

But TransRhodes stepped into a battlefield. Salisbury City Council already had its own transport system ,the Salisbury United Omnibus Company. United had political backing, legal cover, and established routes. Johnstone had ambition, but ambition wasn’t enough.

By 1953, the Council tightened its grip by consolidating operators and formally absorbing fleets under the United group. This eventually turned into a full franchise monopoly within roughly a 26 km radius of the city, renewed well into the 1970s.

Even before that monopoly was fully locked in, Johnstone was clashing with City Council. Reports to Council accused TransRhodes of dropping passengers at unauthorised stops along 3rd Street opposite Cecil Square (now Africa Unity Square).

He was also picking up passengers in the city centre enroute to the authorised terminus ,a direct violation of his operating agreement.

The Council responded by restricting his routes to specific suburbs: the city, Highlands, Meyrick Park, Hatfield, Cranborne, Ardbennie and Prospect. Eventually, Council escalated further and applied to the Governor for exclusive operating rights within twelve miles of the Salisbury Post Office.

Johnstone finally gave up and sold his buses to the United group! Aish!

By the 1970s, Salisbury United had become a world-class operation. The cream-and-red buses became city icons. Timetables were strict. Routes were reliable. Fares were incredibly low ,sometimes as little as 2.5 cents ,thanks to government subsidies.

Under the leadership of Peter Hornblow, the system ran with near-military discipline. Many who lived through that era still say: you could set your watch by a Salisbury United bus.

Then came 1982 ,Salisbury became Harare. Salisbury United became the Zimbabwe United Passenger Company ,Harare United by 1985. The early years still carried the discipline of the old system.

Same drivers, same depots, same maintenance culture. A new flag, but the backbone of the old empire was still there.

But slowly, the winds shifted.

By the late 1980s and 1990s, commuter omnibuses exploded onto the scene ,emergency taxis, cheaper, faster, everywhere at once.

The economy began to strain. Fuel shortages, foreign currency issues, inflation ,all of these hammered a capital-intensive business like public transport. And then came the governance storms.

ZUPCO began experiencing “well-publicised leadership and procurement challenges.” The famous Nherera case became a symbol of the era, dragging ZUPCO’s name through headlines instead of timetables.

By the 2000s, mismanagement, corruption, and economic collapse had eroded what was once a world-class transport system. Buses broke down. Fleets shrank. Queues lengthened. And the memory of Salisbury United’s precision became a painful reminder of how far things had fallen.

The truth is simple: ZUPCO didn’t fail because the idea was wrong. It failed because the environment shifted ,politically, economically, and institutionally. The blueprint for excellence still exists in the old Salisbury United playbook. Zimbabwe just needs the will, discipline, and honesty to resurrect it.